Lime Kilns In Sudan

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks.

/ answered

Question: What role should lime play in the future buildings of Sudan?

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks. Just think of ancient stone temples, columns or statues, or facing stones on more modern buildings. It is less recognizable when crushed or powdered and mixed with other materials like mud or sand. It is easily confused with cement because it looks almost the same – unsurprisingly as cement is made from crushed limestone – but it behaves very differently. It is important to know what these differences are when restoring traditional buildings like the Khalifa House in Omdurman if you want to avoid further damage. In Sudan, restoration techniques can lead to a wider appreciation of local resources and traditional building methods, and ways of using them for today’s climate that don’t cost the earth.

Imagine a Map of lime kilns in Sudan

Archaeologists have discovered that lime and ash were used to make floors many thousands of years ago, even before pottery kilns were invented. Lime is an alkaline material with disinfectant qualities so a good deterrent to bacteria and microorganisms. It is manufactured using fire or heat, which transforms its chemistry. Kilns provide an effective heat source and though they might differ in size and type, they are used to bake bread, fire pots or bricks, work glass, copper, bronze or iron, as well as burn lime. A map could be made of lime kilns in Sudan. It would plot a landscape of human activity that includes quarries, slaking pits, all types of built structures, as well as traces in agricultural land where lime is used as a soil improver.

A lime kiln is very similar to a pottery kiln but, instead of firing pots, pieces of limestone are burnt to produce a white crystalline solid called quicklime. For building purposes, the quicklime is slaked in water and left to rest until it forms a mouldable, easily worked putty which can be used to make plaster, mortar, or used as paint. It can be bulked out with other materials, notably mud or sand, adding to their qualities. Lime dries by absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and chemically speaking turns back into limestone in a process called the lime-cycle. It retains a microscopic crystalline structure (useful in polished finishes) and lots of voids meaning it can breathe air and moisture. At the end of its life the whole process can start over again.

Timeline

If our map showed buildings using lime, it could be used to plot a history. It would tell us lime plaster was used in the stone-built Kushite pyramids and temples. During the Roman period it became popular on the Red Sea coast where there are large deposits of limestone reef beds, high humidity and seasonal rains. Here limestone and lime plasters became an enduring part of the Red Sea style of architecture, exemplified in the iconic buildings of Suakin. During the Christian period lime plaster and mortar were used in the fired brick churches of the Nile Valley, like the Cathedral in Faras and the churches in Dongola and Soba. Similar construction techniques were used in medieval gubbas and the mosques and palace buildings as well as across the Sahel in Darfur and Kordofan. The Ottoman occupation brought more elaborate lime plasterwork techniques and more widespread use until the twentieth century when it was replaced by cement.

Meanwhile, in the drier areas of Sudan, mud bricks, mud mortars were more popular. For example, the later gubbas in the north were built from mud brick and mortar, like the houses and villages. The lack of lime made buildings softer, but a drier atmosphere and reduced rainfall made this less important, until recently. Climate change has made rainfall in Sudan less predictable and more extreme.

Lime kilns, concrete and climate change

Kilns need something to burn and throughout Sudan’s history wood has been the main provider, so forests are needed. Deforestation in Sudan is the result of the drying climate, or an excessive human use of wood, or both. These factors suggest why and when lime stops being used as a building material unless there was an incentive to continue like on the humid Red Sea coast or further south where there are still forests. Our imagined map of lime kilns would show many ruins of kilns in dry or deforested areas. However, it will also show a new breed of limestone burning kilns in the form of modern factories producing cement. These favour water locations over forests.

In Sudan, like most of the world, lime production has been overtaken by cement production as concrete has become the number one building material. Its impact on natural and built landscapes is so enormous it is used as the visual marker of the Anthropocene age, our own geological time frame where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Worldwide this highly refined product has grown to become the biggest consumable after water, the consumption of which it helps drive. Cement is used in infrastructure projects and buildings of all kinds because it has the advantage of strength, durability, and fast production. It is seen as utilitarian because it lends itself to the mass production of office and housing units. It is also fashionable. Concrete is used as a symbol of being modern and it lends itself to realizable fantasy projects, nothing seems too big, too tall or too weird in shape.

In 2018 Sudan was described in SUDANOW magazine as having a booming cement industry with a bright future. The limestone needed was available in many parts of the country and the Nile provided water. The first dam built in Sudan, the Sennar Dam (1925), used uncoursed granite bedded in cement from its on-the-spot new cement factory turning out 1,000 tons of cement a week.

Concrete, however, has its downsides. The production of cement is high on the list of causes of climate change due to its considerable use of water, greenhouse gas emissions (1kg cement = 1kg CO2), fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental damage. However, it was the historic building restoration lobby that first raised the alarm. Historic buildings that had been restored using cement products were failing faster and being damaged by the cement. For although cement seemed to be like lime but better, as it is made from the same basic materials and heating processes, it turns out that it is different rather than better. The way it is made produces different material outcomes.

Khalifa House restoration

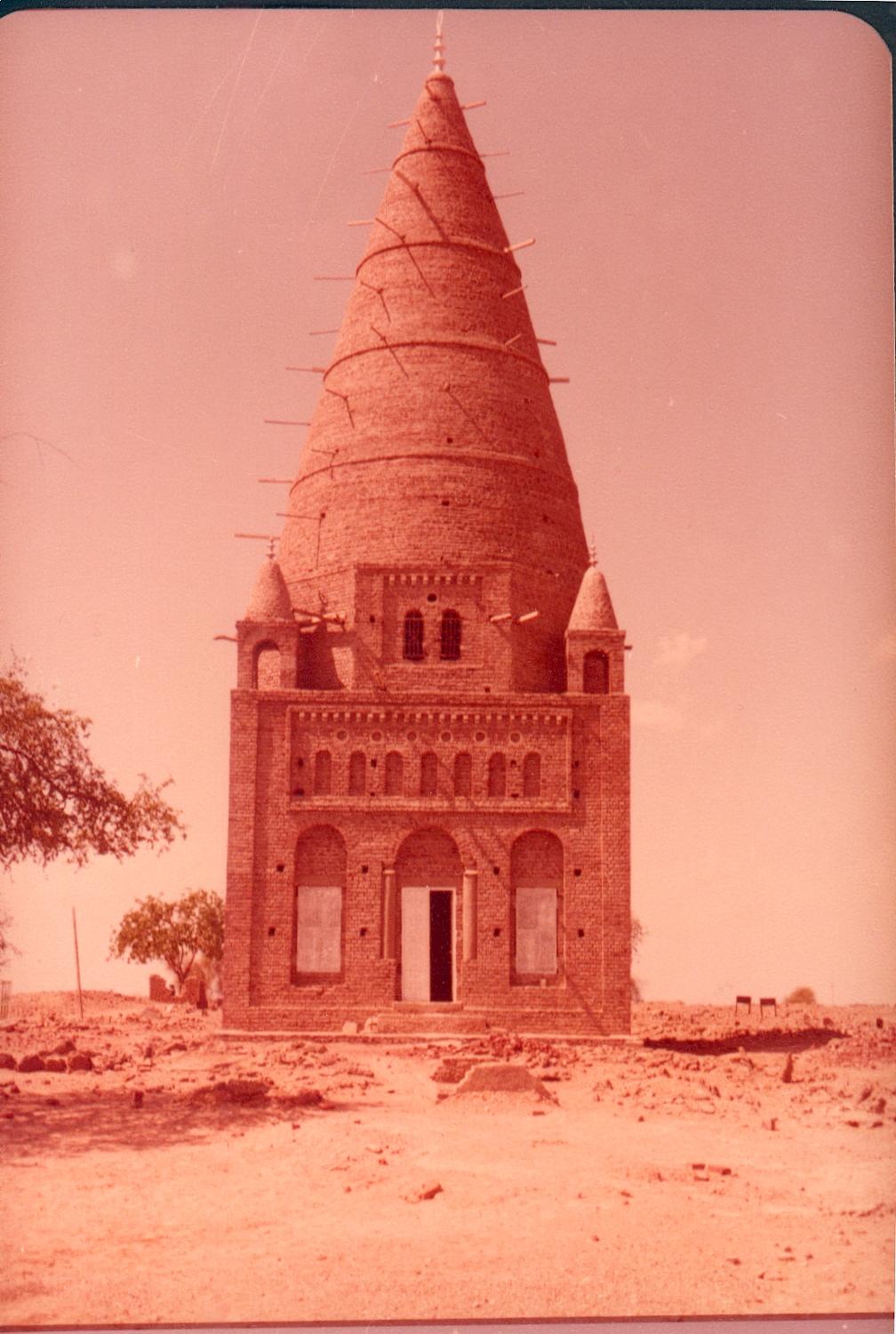

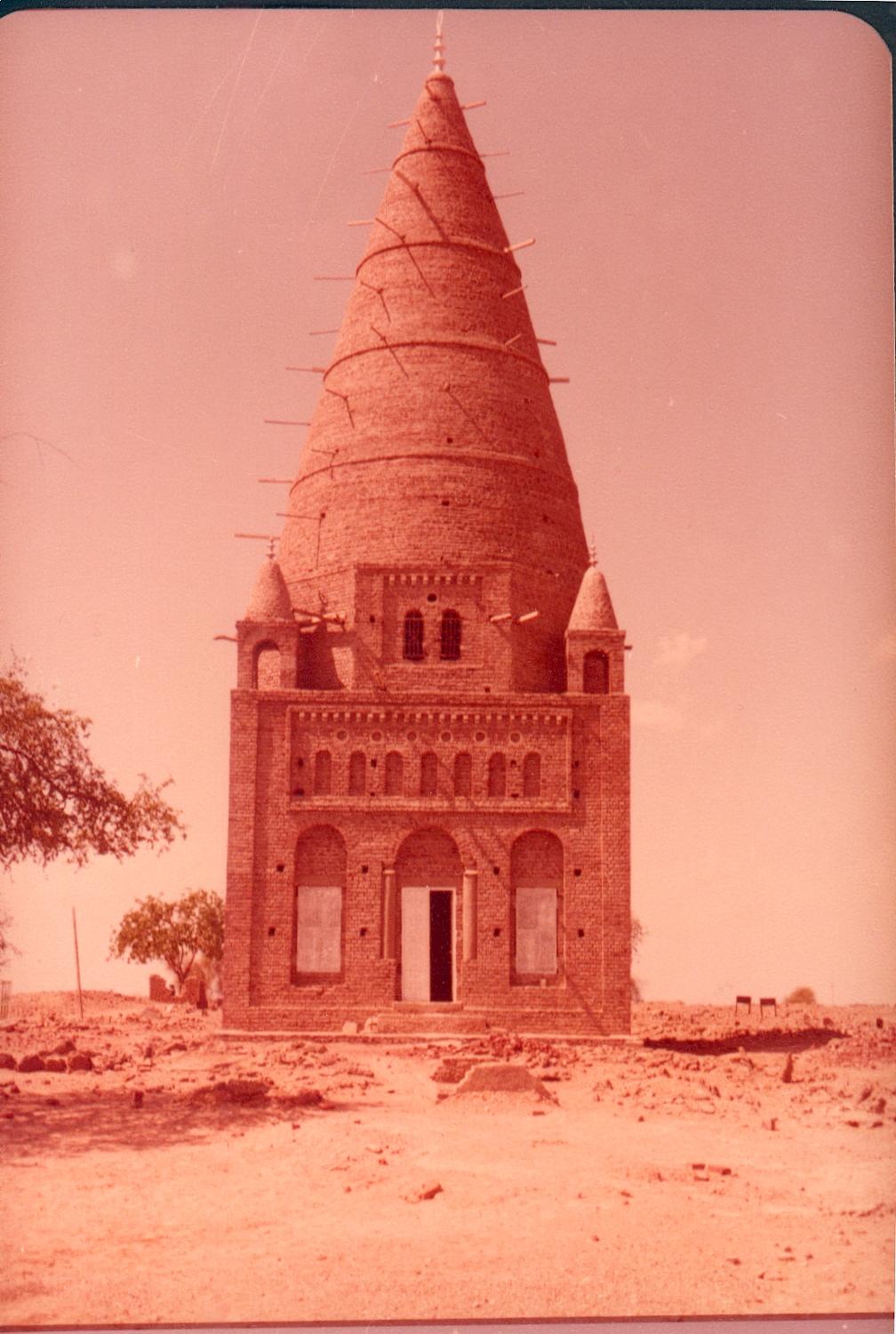

The lime kilns in Omdurman date to the Mahdi period. The Khalifa wanted to build defences strong enough to withstand modern weaponry. The walls in front, and the massive enclosure walls around the Mulazmeen quarter, were 6m high and built with lime and stone. These are the materials used in the first and second phase of construction of the Khalifa House.

The restoration of the Khalifa House in Omdurman started in 2018. The one material not used to restore the building was cement, in fact nearly all traces of it were carefully removed and replaced with lime-based plaster. This was a lot of work as in previous years many of the walls had been repaired and rendered with cement in the belief that they would be better protected. However, because cement is a much harder and an impervious material, it transfers all the problems of movement and moisture to the bricks, mud or stone, and they decay much faster. To restore the Khalifa House properly the builders had to source the lime, slake it in pits and learn the traditional techniques. They did a beautiful job.

The same learning is now being utilised in the ongoing Peace Garden project in Kassala where twelve different house types from all over Sudan are being erected. The team is looking carefully at the use of lime in the mud construction as a way of improving resilience to heavy rainfalls. There are many examples in Sudan of mudbrick buildings that have survived for centuries as well as in other countries around the world, so what is their secret?

Factors to consider

In 2007 work started on the Al Shamal cement factory in Al Damer. Equipped with the latest European technology it also has a solar power plant to supply the factory with lots of clean electricity. The ‘bright future’ claimed for Sudan’s cement industry anticipated two things, Sudan’s participation in a booming market and the development of Sudan itself. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the last empty spaces on the concrete industry project map.

The problem with cement-based materials is they start with a different attitude to life. They are strong and quicker to employ, but less adjusted to living in a natural landscape. They need an extensive infrastructure to work, from quarries to roads, to water and energy, and industrialised systems of supply and demand.

Traditional building techniques in Sudan, on the other hand, are closely tied to the availability of natural resources, local transport, local climate, livelihoods and culture. Lime based materials can help preserve the ecology of living landscapes. Moreover, lime's ability to control moisture means it is compatible with low-energy, sustainable materials, such as water reed, straw, hemp, timber and clay. Lime rather than cement is burnt at 900 degrees rather than 1300 degrees, so less onerous energy-wise and, looking forwards, parabolic solar collectors can be used to fire solar rotary kilns.

The map of lime kilns in Sudan shows the landscape is not empty but full of traditional building types that have been adapting to climate change over a long history. They could play a significant role in adapting to climate change in the future. Not everything is better built in concrete.

Cover picture: Suakin © Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez

Question: What role should lime play in the future buildings of Sudan?

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks. Just think of ancient stone temples, columns or statues, or facing stones on more modern buildings. It is less recognizable when crushed or powdered and mixed with other materials like mud or sand. It is easily confused with cement because it looks almost the same – unsurprisingly as cement is made from crushed limestone – but it behaves very differently. It is important to know what these differences are when restoring traditional buildings like the Khalifa House in Omdurman if you want to avoid further damage. In Sudan, restoration techniques can lead to a wider appreciation of local resources and traditional building methods, and ways of using them for today’s climate that don’t cost the earth.

Imagine a Map of lime kilns in Sudan

Archaeologists have discovered that lime and ash were used to make floors many thousands of years ago, even before pottery kilns were invented. Lime is an alkaline material with disinfectant qualities so a good deterrent to bacteria and microorganisms. It is manufactured using fire or heat, which transforms its chemistry. Kilns provide an effective heat source and though they might differ in size and type, they are used to bake bread, fire pots or bricks, work glass, copper, bronze or iron, as well as burn lime. A map could be made of lime kilns in Sudan. It would plot a landscape of human activity that includes quarries, slaking pits, all types of built structures, as well as traces in agricultural land where lime is used as a soil improver.

A lime kiln is very similar to a pottery kiln but, instead of firing pots, pieces of limestone are burnt to produce a white crystalline solid called quicklime. For building purposes, the quicklime is slaked in water and left to rest until it forms a mouldable, easily worked putty which can be used to make plaster, mortar, or used as paint. It can be bulked out with other materials, notably mud or sand, adding to their qualities. Lime dries by absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and chemically speaking turns back into limestone in a process called the lime-cycle. It retains a microscopic crystalline structure (useful in polished finishes) and lots of voids meaning it can breathe air and moisture. At the end of its life the whole process can start over again.

Timeline

If our map showed buildings using lime, it could be used to plot a history. It would tell us lime plaster was used in the stone-built Kushite pyramids and temples. During the Roman period it became popular on the Red Sea coast where there are large deposits of limestone reef beds, high humidity and seasonal rains. Here limestone and lime plasters became an enduring part of the Red Sea style of architecture, exemplified in the iconic buildings of Suakin. During the Christian period lime plaster and mortar were used in the fired brick churches of the Nile Valley, like the Cathedral in Faras and the churches in Dongola and Soba. Similar construction techniques were used in medieval gubbas and the mosques and palace buildings as well as across the Sahel in Darfur and Kordofan. The Ottoman occupation brought more elaborate lime plasterwork techniques and more widespread use until the twentieth century when it was replaced by cement.

Meanwhile, in the drier areas of Sudan, mud bricks, mud mortars were more popular. For example, the later gubbas in the north were built from mud brick and mortar, like the houses and villages. The lack of lime made buildings softer, but a drier atmosphere and reduced rainfall made this less important, until recently. Climate change has made rainfall in Sudan less predictable and more extreme.

Lime kilns, concrete and climate change

Kilns need something to burn and throughout Sudan’s history wood has been the main provider, so forests are needed. Deforestation in Sudan is the result of the drying climate, or an excessive human use of wood, or both. These factors suggest why and when lime stops being used as a building material unless there was an incentive to continue like on the humid Red Sea coast or further south where there are still forests. Our imagined map of lime kilns would show many ruins of kilns in dry or deforested areas. However, it will also show a new breed of limestone burning kilns in the form of modern factories producing cement. These favour water locations over forests.

In Sudan, like most of the world, lime production has been overtaken by cement production as concrete has become the number one building material. Its impact on natural and built landscapes is so enormous it is used as the visual marker of the Anthropocene age, our own geological time frame where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Worldwide this highly refined product has grown to become the biggest consumable after water, the consumption of which it helps drive. Cement is used in infrastructure projects and buildings of all kinds because it has the advantage of strength, durability, and fast production. It is seen as utilitarian because it lends itself to the mass production of office and housing units. It is also fashionable. Concrete is used as a symbol of being modern and it lends itself to realizable fantasy projects, nothing seems too big, too tall or too weird in shape.

In 2018 Sudan was described in SUDANOW magazine as having a booming cement industry with a bright future. The limestone needed was available in many parts of the country and the Nile provided water. The first dam built in Sudan, the Sennar Dam (1925), used uncoursed granite bedded in cement from its on-the-spot new cement factory turning out 1,000 tons of cement a week.

Concrete, however, has its downsides. The production of cement is high on the list of causes of climate change due to its considerable use of water, greenhouse gas emissions (1kg cement = 1kg CO2), fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental damage. However, it was the historic building restoration lobby that first raised the alarm. Historic buildings that had been restored using cement products were failing faster and being damaged by the cement. For although cement seemed to be like lime but better, as it is made from the same basic materials and heating processes, it turns out that it is different rather than better. The way it is made produces different material outcomes.

Khalifa House restoration

The lime kilns in Omdurman date to the Mahdi period. The Khalifa wanted to build defences strong enough to withstand modern weaponry. The walls in front, and the massive enclosure walls around the Mulazmeen quarter, were 6m high and built with lime and stone. These are the materials used in the first and second phase of construction of the Khalifa House.

The restoration of the Khalifa House in Omdurman started in 2018. The one material not used to restore the building was cement, in fact nearly all traces of it were carefully removed and replaced with lime-based plaster. This was a lot of work as in previous years many of the walls had been repaired and rendered with cement in the belief that they would be better protected. However, because cement is a much harder and an impervious material, it transfers all the problems of movement and moisture to the bricks, mud or stone, and they decay much faster. To restore the Khalifa House properly the builders had to source the lime, slake it in pits and learn the traditional techniques. They did a beautiful job.

The same learning is now being utilised in the ongoing Peace Garden project in Kassala where twelve different house types from all over Sudan are being erected. The team is looking carefully at the use of lime in the mud construction as a way of improving resilience to heavy rainfalls. There are many examples in Sudan of mudbrick buildings that have survived for centuries as well as in other countries around the world, so what is their secret?

Factors to consider

In 2007 work started on the Al Shamal cement factory in Al Damer. Equipped with the latest European technology it also has a solar power plant to supply the factory with lots of clean electricity. The ‘bright future’ claimed for Sudan’s cement industry anticipated two things, Sudan’s participation in a booming market and the development of Sudan itself. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the last empty spaces on the concrete industry project map.

The problem with cement-based materials is they start with a different attitude to life. They are strong and quicker to employ, but less adjusted to living in a natural landscape. They need an extensive infrastructure to work, from quarries to roads, to water and energy, and industrialised systems of supply and demand.

Traditional building techniques in Sudan, on the other hand, are closely tied to the availability of natural resources, local transport, local climate, livelihoods and culture. Lime based materials can help preserve the ecology of living landscapes. Moreover, lime's ability to control moisture means it is compatible with low-energy, sustainable materials, such as water reed, straw, hemp, timber and clay. Lime rather than cement is burnt at 900 degrees rather than 1300 degrees, so less onerous energy-wise and, looking forwards, parabolic solar collectors can be used to fire solar rotary kilns.

The map of lime kilns in Sudan shows the landscape is not empty but full of traditional building types that have been adapting to climate change over a long history. They could play a significant role in adapting to climate change in the future. Not everything is better built in concrete.

Cover picture: Suakin © Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez

.svg)