The moving land

What does the city mean? How can land move? What can we learn from the nomadic lifestyle?

.jpeg)

/ answered

What does a city mean? When we asked a resident of Old Haj Yousif if he considered his neighborhood to be a city, he said yes. We asked why, and he said it was because foreigners were now moving into the neighborhood. Haj Yousif was an urban village to the north of Khartoum that was absorbed by the city's urban expansion. I asked the same question to a resident of Alshigailab, another village that the city stretched into in recent years. His answer was that the changing livelihoods of the residents and the replanning of their village made it a city. Governments also have their own ways of deciding what a city is. Usually, the number of residents in one area of land is the key indicator; sometimes it is the types and scale of services, which are also determined by the population density of a particular geographical area. Services are placed to serve a specific catchment area. However, a unanimous understanding of a city is that it’s a fixed piece of land that expands, grows, and changes for various reasons, including sociopolitical changes.

The events of 2024 in Sudan are game-changing. By April 2024, exactly one year after the beginning of the war, over ten million people had been displaced, approximately a quarter of Sudan's entire population, according to IOM estimates. This is the population size of a megacity or twenty or so regular-sized cities. The use of a city as a measurement is critical here, as for cities to exist and be sustained, they require a certain level of infrastructure, capacity, governance, food production, and basic services. Over 80% of the displaced individuals are still within Sudan, integrating into other already extremely undeveloped villages, towns, and small cities. They are straining the capacity of these settlements and threatening the entire country with the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, and a critical state of food security and famine.

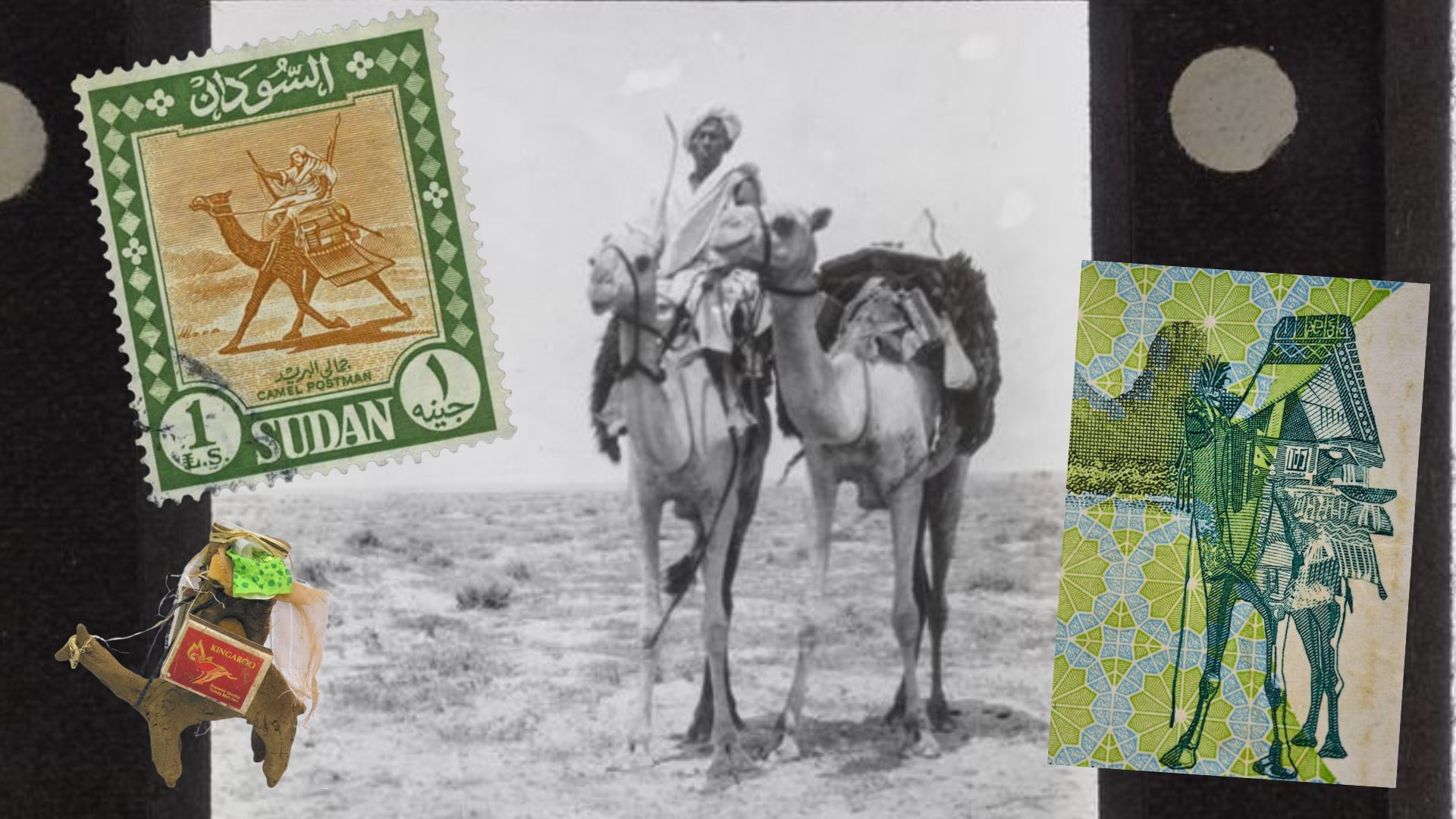

Now let's take a different angle and look at the same issue. The majority of the displaced population are urban residents fleeing three of the largest cities in Sudan: Khartoum, Wadi Madani, and Nyala. However, the largest population of Sudan is actually rural, such as farmers and pastoralists. These communities have also been affected by the conflict as the war has disrupted their livelihoods, lifestyles, and routes of movement. However, a comparison between nomadic lifestyle, which involves voluntary movement, and conflict-induced movement is worth mentioning.

Nomads move in large numbers, often accompanied by their livestock, which can cover the area of small settlements. Like the current displaced people, the nomadic populations can also be considered moving pieces of land. Pastoralists have been roaming the earth for centuries, if not millennia. They function to a large extent like a regular fixed settlement, growing and shrinking in size. They have full moving services catered to this number of people and animals, even though the type of required infrastructure for nomadism is obviously different from a settled settlement. They still have medical and environmental experts, routes of movement, housing, and governance.

Communal and customary land laws are a very complicated issue, so it would not be feasible to include them in this writing. However, the land required to house all the needs of nomads will always be there. If we take land use or the right to occupy land for certain amounts of time as a form of temporary ownership, this seasonal ownership that occurs every year for years creates boundaries of customary agreements and encroachments. The use in question and how resources are shared are some of the many originating causes of disagreements. But these frameworks also hold potential answers to current issues. Borrowing frameworks from these lifestyles can help tackle current issues of displacement. How do cities move? What could make a city on four legs? What if people continue to move? How can urban experts learn from the rural?

What does a city mean? When we asked a resident of Old Haj Yousif if he considered his neighborhood to be a city, he said yes. We asked why, and he said it was because foreigners were now moving into the neighborhood. Haj Yousif was an urban village to the north of Khartoum that was absorbed by the city's urban expansion. I asked the same question to a resident of Alshigailab, another village that the city stretched into in recent years. His answer was that the changing livelihoods of the residents and the replanning of their village made it a city. Governments also have their own ways of deciding what a city is. Usually, the number of residents in one area of land is the key indicator; sometimes it is the types and scale of services, which are also determined by the population density of a particular geographical area. Services are placed to serve a specific catchment area. However, a unanimous understanding of a city is that it’s a fixed piece of land that expands, grows, and changes for various reasons, including sociopolitical changes.

The events of 2024 in Sudan are game-changing. By April 2024, exactly one year after the beginning of the war, over ten million people had been displaced, approximately a quarter of Sudan's entire population, according to IOM estimates. This is the population size of a megacity or twenty or so regular-sized cities. The use of a city as a measurement is critical here, as for cities to exist and be sustained, they require a certain level of infrastructure, capacity, governance, food production, and basic services. Over 80% of the displaced individuals are still within Sudan, integrating into other already extremely undeveloped villages, towns, and small cities. They are straining the capacity of these settlements and threatening the entire country with the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, and a critical state of food security and famine.

Now let's take a different angle and look at the same issue. The majority of the displaced population are urban residents fleeing three of the largest cities in Sudan: Khartoum, Wadi Madani, and Nyala. However, the largest population of Sudan is actually rural, such as farmers and pastoralists. These communities have also been affected by the conflict as the war has disrupted their livelihoods, lifestyles, and routes of movement. However, a comparison between nomadic lifestyle, which involves voluntary movement, and conflict-induced movement is worth mentioning.

Nomads move in large numbers, often accompanied by their livestock, which can cover the area of small settlements. Like the current displaced people, the nomadic populations can also be considered moving pieces of land. Pastoralists have been roaming the earth for centuries, if not millennia. They function to a large extent like a regular fixed settlement, growing and shrinking in size. They have full moving services catered to this number of people and animals, even though the type of required infrastructure for nomadism is obviously different from a settled settlement. They still have medical and environmental experts, routes of movement, housing, and governance.

Communal and customary land laws are a very complicated issue, so it would not be feasible to include them in this writing. However, the land required to house all the needs of nomads will always be there. If we take land use or the right to occupy land for certain amounts of time as a form of temporary ownership, this seasonal ownership that occurs every year for years creates boundaries of customary agreements and encroachments. The use in question and how resources are shared are some of the many originating causes of disagreements. But these frameworks also hold potential answers to current issues. Borrowing frameworks from these lifestyles can help tackle current issues of displacement. How do cities move? What could make a city on four legs? What if people continue to move? How can urban experts learn from the rural?

.svg)

.jpeg)